Autores

Colombian Art: Academic Affirmation and Landscaping

Colombian Art: Academic Affirmation and Landscaping

Article by: Santiago Londono Velez

Cover Article: Gonzalo Ariza

from the book: COLOMBIAN ART 3,500 years of history

While the Bachués and the Pedronelistas led the avant-garde of Colombian art, a group of artists reacted against what they considered excessive indigenism and against the inclination towards revolutionary and political art. They took up themes such as portraiture, landscape, still life and scenes of customs, reinterpreting them with resources taken from conventional French and Spanish painting, thus adapting the old pictorial genres to the taste of the most conservative sectors of the moment. As the commentator Rafael Tavera wrote in 1920 , to explain the fashionable preference for Iberian painting, “...our things are things from Spain.”

“...our things are things from Spain.”

- Rafael Tavera

Miguel Díaz Vargas (1886-1956), with his accumulations of domestic objects and farm products present in popular markets, as in Bodegón (ca. 1935) and Bodegón (1953), sings in an idealized way to the fruits of a bucolic land fertile. In his own words, he liked to paint “...the domestic scenes of poor people”, without it being a painting committed to social problems. His contemporary was the Santander native Domingo Moreno Otero (1882-1948), who shared the same thematic interest as Díaz and, like him, graduated from the San Fernando Academy in Madrid.

Ricardo Gómez Campuzano (1893-1981) studied in Bogotá and Madrid; In addition to being a landscape painter who extended the turn-of-the-century tradition of the genre over time, he was also an accomplished painter of society portraits, refreshed with a modernizing treatment within the so-called “Spanishness,” a stylistic inclination that he knew how to impose based on the teachings he he received at the San Fernando Academy in Madrid, as seen in The Painter Eugenio Peña (1930). José Rodríguez Acevedo (1907-1981), within the renewal of academic portraiture, used a brightly colored palette and was interested in mestizo human types, represented with fidelity and taste for decorative elements, as in Two Women (1951) and Face of girl (1951), in which questions about the enigmas of female psychology are found.

In Antioquia, Eladio Vélez led the reaction against the Pedronelistas. With his followers, he insisted on painting isolated from social problems and concentrated on plastic matters and classical themes such as portraiture, landscape and still lifes. Marina (Viareggio, Italy) (1928), painted during his training in Europe, and Landscape (1939), made in Antioquia, exemplify his academic and coloristic proposal, which turns out to be a development of the postulates of the school of maestro Cano. , and an opposition to aesthetics at the service of the less fortunate, advocated by Pedro Nel Gómez and his followers.

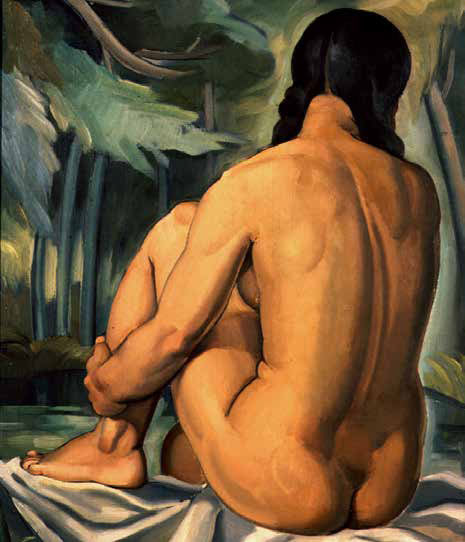

Ignacio Gómez Jaramillo (1910-1970), trained in Spain, at first seemed to align himself with the followers of Eladio Vélez, but later opted for a personal style of quality that was not always consistent. In the subject matter of his controversial murals he approached the Bachués and the Pedronelistas. In his drawings and oil paintings he represented landscapes and, preferably, the female figure, characterized by its solid volumetry, generally arranged in a context that, despite its naturalistic references, often seems dreamlike. Concerned about artistic fashions, in the 1960s he tried out themes such as roosters and clowns, very popular at the time, under the influence of the Frenchman Bernard Buffett, as well as compositions with abstract intentions. Back (ca. 1940) illustrates well his female prototypes, with strong body construction, copper skin and cold contemplative sensuality.

Ignacio Gomez Jaramillo

Back / 1940/ Oil on canvas

As a young man, Gonzalo Ariza (1912-1995) traveled to Japan to study for four years, perhaps as a way of escaping the attraction then exerted by the European avant-garde and the ideological dictates of the Bachués and the Pedronelistas. Until then, he had produced an outstanding series of linoleum illustrations, depicting popular issues with evident Mexican influence. Upon returning to Colombia, he developed an extensive work that is a sensitive tribute to the native landscape. It is typified in the atmospheres, whether veiled by mist, dense or transparent, taken from nature in the different climates of the country; In his words, “I have personally been interested in landscape as a way of expression and because it is the most unique and authentic thing we have.” All of this can be seen in Aserríos en el Chocó (1956), a large, meticulously crafted aerial view of the jungle, and in Moonlight Night in Faca (ca. 1960). Ariza was also a flower painter and participated in numerous exhibitions, despite the fact that the rise of avant-garde movements such as nationalism and abstractionism intransigently and relentlessly relegated him from the Colombian art scene.

Gonzalo Ariza

(Bogotá, 1912 - Bogotá, 1995)

Sawmills in Chocó (detail).

1956 Oil on canvas. 180x298cm

Bank of the Republic Collection